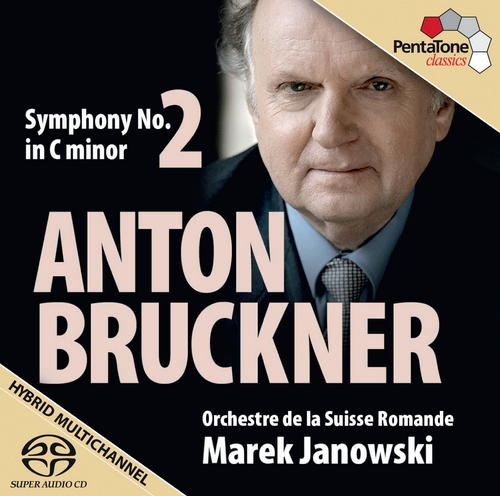

Wydawnictwo: Pentatone

Seria: Bruckner Works / Janowski

Nr katalogowy: PTC 5186448

Nośnik: 1 SACD

Data wydania: lipiec 2013

EAN: 827949044861

Seria: Bruckner Works / Janowski

Nr katalogowy: PTC 5186448

Nośnik: 1 SACD

Data wydania: lipiec 2013

EAN: 827949044861

Bruckner: Symphony No. 2 in C minor (Version 1877)

Pentatone - PTC 5186448

Kompozytor

Anton Bruckner (1824-1896)

Anton Bruckner (1824-1896)

Utwory na płycie:

Symphony No. 2: I. Moderato

Symphony No. 2: I. Moderato Symphony No. 2: II. Andante: Feierlich, etwas bewegt

Symphony No. 2: II. Andante: Feierlich, etwas bewegt Symphony No. 2: III. Scherzo: Massig schnell

Symphony No. 2: III. Scherzo: Massig schnell Symphony No. 2: IV. Finale: Mehr schnell

Symphony No. 2: IV. Finale: Mehr schnell

00:00/00:00

Error loading: "music/pentatone/ptc5186448/ptc5186448_01.mp3"

Symphonic "test-drilling"

To this day, Anton Bruckner's Symphony No. 2 in C minor is the least frequently performed of all his symphonies. Rather odd, as the composer described the work in a letter dated October 9, 1878 as "probably, first and foremost, the symphony that is easiest for the audience to understand", and the first performance, given in Vienna on October 16, 1873 was a great success for the composer. How can one explain this peculiar contrast? On the one hand, considered objectively, the audience could easily follow the work; yet on the other hand, the public at large displayed a predominant lack of interest in the symphony. Is there more involved in this case to fully comprehend precisely this symphony, than simply an understanding of its very clear formal concept? Or had the Symphony No. 2 simply fallen between two creative stools, thanks to its direct symphonic predecessors and successors? Let us take a brief look at the works in its direct vicinity.

Bruckner's Symphony No. 1, the famous "saucy maid", had been a symphonic début such as the world had not seen since Beethoven and Berlioz. A début full of radicalism and innovation, in which new ground was broken by Bruckner. However, his Symphony No. 3 is regarded as his (symphonic) problem child. Well-loved, yet not necessarily successful. In its first version, it is a gigantic, megalomaniac work. Well, the Symphony No. 2 is situated between these two extremes. Not as revolutionary as the first, nor as brutally out of hand as the third. In the musicological writings about the work, one comes across the description "retarding factor" (Manfred Wagner). A highly accurate formulation, however, one that requires a more in-depth explanation with regard to the further compositional development of the composer's personal concept of the symphony, which received a massive push forward in the second symphony. For the Symphony No. 2 is not a "step backwards", as Dietmar Holland also stresses, but rather a highly independent "symphonic creature", thanks to its characteristic "bulkiness" and the high level of complexity of its content. Not only is the Symphony No. 2 the first of his symphonies to be composed in Vienna, it is also the first true manifestation of the ubiquitous problem of his multiple versions of one and the same work (though certainly not in its clearest expression). For a person like Bruckner, Vienna appears to have been a difficult place; the rapidly growing city was going through a phase of dramatic and radical changes (for instance, those brought about by various architectural feats). And Bruckner seems to have been "initially quite cowed" by the city of Vienna. In the years 1869 and 1871, he enjoyed great success as a virtuoso organist in France and England, but on his return to Vienna – a city rife with intrigue – he was immediately confronted with disciplinary proceedings of an almost grotesque nature (which were later dropped) for the alleged sexual harassment of a student. Not the best conditions under which to liberate the mind for the composition of a symphony. In October 1871, Bruckner began work on his second symphony. He finished the first movement on July 8, 1872, completing the remainder of the score in just two months on September 11, 1872; and the following month, the first rehearsals with the Vienna Philharmonic took place. However, the conductor for the subscription concerts, Otto Dessoff, rejected the work rigorously as being unplayable. A year later, Bruckner made another attempt at staging the work. This time, he hired the Vienna Philharmonic and himself conducted the first performance on October 26, 1873 during the closing ceremony of the Vienna World Exhibition. This was a great success, not only with the audience, but also with the orchestra (!). The reviews of the premiere already make reference in words and style to the aesthetic dispute between the New German School and the conservatives, which would become an increasingly stressful topic for Bruckner from now on: with his followers lapsing into adulation, and his critics into taunts and mockery. Despite the mainly positive reception of the work, Bruckner followed the advice of his patron and benefactor, Johann Herbeck, and undertook a profound revision of his symphony, which consisted mainly of cuts. The work was subsequently performed in this form on February 20, 1876, again with the Vienna Philharmonic. Once again, with partially enthusiastic waves of applause from the Bruckner fans. In 1877, Bruckner again completed a revision of his second symphony, and in 1892 further adjustments were carried out under his guidance before the work went to print. Thus, one can speak of three versions of the work: 1871-1872, 1873-1877, and 1892. For many decades, the Symphony No. 2 – which was published in Robert Haas' "Alte Gesamtausgabe" (= old complete edition) in 1938 – was presented as a mix of the different versions and referred to as the "ideal version", or the "original version". Not until a few years ago were the versions from 1872 and 1877 presented in two volumes as part of William Carragan's "Neue Gesamtausgabe" (= new complete edition), and this recording is based on the latter. (For details concerning the versions, please refer to William Carragan's preface to the NGA, referring to the 1877 version.) Bruckner's core theme in his Symphony No. 2 is the continued testing, exploration, and expansion of the symphonic possibilities. One could regard this process of testing as a type of archaeological "test-drilling", during which the researcher-composer penetrates deeper into strata never yet observed by man. With the significant difference that Bruckner is looking to the future, whereas the archaeologist is staring at the past. Bruckner's vision of the future of the symphony becomes more precise, sharper, and increasingly rounded as he completes each symphony. The concept of "work in progress", i.e. the reworking and refining of a concept can certainly be applied to the Symphony No. 2. In addition to the pair of symphonies in D minor (the Symphony No. 0 and the Symphony No. 3), Bruckner created a second pair of symphonies, this time written in C minor (his Symphony No. 1 and Symphony No. 2). Both latter works mentioned in each pair (i.e. the second and third symphonies) seem to represent a kind of recourse to the earlier works (the zero and first symphonies) written in the same key; they are a more elaborate development of the first concepts. Albeit with varying results.

The first movement of the Symphony No. 2 is in sonata form; furthermore, as is usual with Bruckner, it establishes three groups of themes in the exposition, including transition. For the first time here, the tremolo beginning is heard in the high strings, providing a heavenly – as it were – basis for the thematic nucleus of the movement, which forms the main theme. Furthermore, this is a chromatic semitone figure in the cellos with the characteristics of a double leading tone. The subsequent ascending scale element in the woodwinds provides a first intensification, which is replaced by a third theme – a strange, seemingly extraterritorial trumpet fanfare in the "Bruckner rhythm" (2:3). Shades of Gustav Mahler... Wolfram Steinbeck has argued conclusively that "the development of the themes as such already includes within itself the process of the symphonic development". The group of song-themes exhibits the peculiar concept of double themes, which is so specific to Bruckner: it is never clear exactly which voice has the leading theme. This is followed by the unison group of themes, which leads to a first climax, continually "pierced", as it were, by the trumpet fanfare, until the climax comes to an abrupt halt. The epilogue with its intense oboe melody feels – in stark contrast to the Symphony No. 1, which uses a heroic trombone entrance in the same place – like a moment of silence, of contemplation, of pause, of resignation, before the development commences. In this section, a permanent compression of motivic and thematic elements takes place, caused partially by the combination of parts of different themes. Before the rather unsurprising recapitulation, one of those numerous general pauses occurs, due to which the second symphony has been saddled with the – one has to admit – unfair nickname of the Symphony of Pauses. For in no way do these pauses simply demarcate the borders between the structural elements characteristic of the genre: rather, they constitute an "energy buffer" in which the power of the music continues to throb inaudibly, and is recharged, as it were, with new energy. (In the 1877 version, these pauses are eliminated in various significant places.) The coda leads in two enormous, swelling waves towards its final fff destination, while chanting the fanfare motif from the main theme group.

The Andante – which in the 1871-72 version still occupied the place of the third movement as the Adagio – strikes up the sacral tone that would from now onwards more or less determine all slow movements in Bruckner's symphonies. Not only does Bruckner create a mystical tension by means of the "tritone suspense" of the second theme (which is structured as a double theme, as are the song-themes of the other movements), he also – and mainly – refers to a quasi-religious tone in this movement by means of quotes from the Benedictus (taken from the Mass in F minor, which was premiered in 1872) placed at the transition points before the beginning of the reprise and the coda. Even if one does not understand or recognize the almost literal borrowing of music from the mass as "quotes", the desired chorale-like and sacred character of the music is defined by precisely these sounds. But Bruckner also incorporated the structural layout of this slow movement in the symphonies following his Symphony No. 2 (with the exception of the sixth), thus dictating their form: with two themes in the exposition, the middle section as a kind of development, and a recapitulation excluding the main theme plus coda. Despite its traditional concepts, this is really no longer a sonata form: yet neither is it a pure A-B-A form. Rather, it is a form that applies itself primarily to intensification, with a climax in the recapitulation, followed by a calm and contemplative ending to the movement.

The Scherzo extracts its thematic content from the stamp-bump rhythm of the unison main theme (two quavers on the first beat of the following crotchet impulses), which makes use diastematically of the minor second interval from the main motif of the first movement. Here, the music is wild and aggressive; the rhythmic theme incessantly works its way through the movement; the trio is a Ländler with phases dominated by the woodwind. Bruckner shortened his 1877 version mainly by eliminating the internal repeats. The general pause following the repetition of the Scherzo has a simply surprising and overwhelming effect, when the coda abruptly bursts in and the theme undergoes a final intensification.

Tremendous cuts were made in the finale of the 1877 version, with a mere 613 bars remaining of the original 806. Bruckner also eliminated a few general pauses at various transition points in the symphony, as well as 55 bars in the development (which he replaced by a "new section" [Bruckner]); furthermore, the "Eleison" quote disappeared with the transition to the coda, "as well as the entire first characteristic intensification, including the quotes from the first movement and the finale; so that in the second version, only the final intensification remains, without the intrinsically typical interruption" (Steinbeck). The final movement begins with an intensification, at the end of which the main theme breaks through for the first time in ff, and unison in the orchestra. A quaver-triplet is heard on the first beat, followed by "stamping crotchet notes". A second attempt is also broken off and makes place for the, once again, double-themed song-theme, written in the mediant key of A major, which is again replaced by a kind of fake unison theme, which is merely a variation of the main theme. This presses onward in three attempts to further outbreaks, until a quote from the Kyrie of the Mass in F minor finally resolves the accumulated tension and creates a deep sense of peace. After an extended development and the recapitulation, written in accordance with the rules, Bruckner dedicates himself to the heart of the composition in the coda. Here, he provides the solution not only for the movement, but for the work as a whole: the main themes of the finale and the first movement (with the fanfare-Bruckner-rhythm, which earlier felt strangely out of context in the opening movement) are combined and are brought to a final superlative ending. Bruckner did not consider this work complete without the addition of essential elements from the beginning – namely the main theme and fanfare rhythm from the first movement. And the same was valid for all his following symphonies. The beginning and the end are intermeshed. They are mutually dependent. They fulfil one another; here, in the radiant key of C major. This symphony does not fall between the creative stools – rather, it occupies its own

To this day, Anton Bruckner's Symphony No. 2 in C minor is the least frequently performed of all his symphonies. Rather odd, as the composer described the work in a letter dated October 9, 1878 as "probably, first and foremost, the symphony that is easiest for the audience to understand", and the first performance, given in Vienna on October 16, 1873 was a great success for the composer. How can one explain this peculiar contrast? On the one hand, considered objectively, the audience could easily follow the work; yet on the other hand, the public at large displayed a predominant lack of interest in the symphony. Is there more involved in this case to fully comprehend precisely this symphony, than simply an understanding of its very clear formal concept? Or had the Symphony No. 2 simply fallen between two creative stools, thanks to its direct symphonic predecessors and successors? Let us take a brief look at the works in its direct vicinity.

Bruckner's Symphony No. 1, the famous "saucy maid", had been a symphonic début such as the world had not seen since Beethoven and Berlioz. A début full of radicalism and innovation, in which new ground was broken by Bruckner. However, his Symphony No. 3 is regarded as his (symphonic) problem child. Well-loved, yet not necessarily successful. In its first version, it is a gigantic, megalomaniac work. Well, the Symphony No. 2 is situated between these two extremes. Not as revolutionary as the first, nor as brutally out of hand as the third. In the musicological writings about the work, one comes across the description "retarding factor" (Manfred Wagner). A highly accurate formulation, however, one that requires a more in-depth explanation with regard to the further compositional development of the composer's personal concept of the symphony, which received a massive push forward in the second symphony. For the Symphony No. 2 is not a "step backwards", as Dietmar Holland also stresses, but rather a highly independent "symphonic creature", thanks to its characteristic "bulkiness" and the high level of complexity of its content. Not only is the Symphony No. 2 the first of his symphonies to be composed in Vienna, it is also the first true manifestation of the ubiquitous problem of his multiple versions of one and the same work (though certainly not in its clearest expression). For a person like Bruckner, Vienna appears to have been a difficult place; the rapidly growing city was going through a phase of dramatic and radical changes (for instance, those brought about by various architectural feats). And Bruckner seems to have been "initially quite cowed" by the city of Vienna. In the years 1869 and 1871, he enjoyed great success as a virtuoso organist in France and England, but on his return to Vienna – a city rife with intrigue – he was immediately confronted with disciplinary proceedings of an almost grotesque nature (which were later dropped) for the alleged sexual harassment of a student. Not the best conditions under which to liberate the mind for the composition of a symphony. In October 1871, Bruckner began work on his second symphony. He finished the first movement on July 8, 1872, completing the remainder of the score in just two months on September 11, 1872; and the following month, the first rehearsals with the Vienna Philharmonic took place. However, the conductor for the subscription concerts, Otto Dessoff, rejected the work rigorously as being unplayable. A year later, Bruckner made another attempt at staging the work. This time, he hired the Vienna Philharmonic and himself conducted the first performance on October 26, 1873 during the closing ceremony of the Vienna World Exhibition. This was a great success, not only with the audience, but also with the orchestra (!). The reviews of the premiere already make reference in words and style to the aesthetic dispute between the New German School and the conservatives, which would become an increasingly stressful topic for Bruckner from now on: with his followers lapsing into adulation, and his critics into taunts and mockery. Despite the mainly positive reception of the work, Bruckner followed the advice of his patron and benefactor, Johann Herbeck, and undertook a profound revision of his symphony, which consisted mainly of cuts. The work was subsequently performed in this form on February 20, 1876, again with the Vienna Philharmonic. Once again, with partially enthusiastic waves of applause from the Bruckner fans. In 1877, Bruckner again completed a revision of his second symphony, and in 1892 further adjustments were carried out under his guidance before the work went to print. Thus, one can speak of three versions of the work: 1871-1872, 1873-1877, and 1892. For many decades, the Symphony No. 2 – which was published in Robert Haas' "Alte Gesamtausgabe" (= old complete edition) in 1938 – was presented as a mix of the different versions and referred to as the "ideal version", or the "original version". Not until a few years ago were the versions from 1872 and 1877 presented in two volumes as part of William Carragan's "Neue Gesamtausgabe" (= new complete edition), and this recording is based on the latter. (For details concerning the versions, please refer to William Carragan's preface to the NGA, referring to the 1877 version.) Bruckner's core theme in his Symphony No. 2 is the continued testing, exploration, and expansion of the symphonic possibilities. One could regard this process of testing as a type of archaeological "test-drilling", during which the researcher-composer penetrates deeper into strata never yet observed by man. With the significant difference that Bruckner is looking to the future, whereas the archaeologist is staring at the past. Bruckner's vision of the future of the symphony becomes more precise, sharper, and increasingly rounded as he completes each symphony. The concept of "work in progress", i.e. the reworking and refining of a concept can certainly be applied to the Symphony No. 2. In addition to the pair of symphonies in D minor (the Symphony No. 0 and the Symphony No. 3), Bruckner created a second pair of symphonies, this time written in C minor (his Symphony No. 1 and Symphony No. 2). Both latter works mentioned in each pair (i.e. the second and third symphonies) seem to represent a kind of recourse to the earlier works (the zero and first symphonies) written in the same key; they are a more elaborate development of the first concepts. Albeit with varying results.

The first movement of the Symphony No. 2 is in sonata form; furthermore, as is usual with Bruckner, it establishes three groups of themes in the exposition, including transition. For the first time here, the tremolo beginning is heard in the high strings, providing a heavenly – as it were – basis for the thematic nucleus of the movement, which forms the main theme. Furthermore, this is a chromatic semitone figure in the cellos with the characteristics of a double leading tone. The subsequent ascending scale element in the woodwinds provides a first intensification, which is replaced by a third theme – a strange, seemingly extraterritorial trumpet fanfare in the "Bruckner rhythm" (2:3). Shades of Gustav Mahler... Wolfram Steinbeck has argued conclusively that "the development of the themes as such already includes within itself the process of the symphonic development". The group of song-themes exhibits the peculiar concept of double themes, which is so specific to Bruckner: it is never clear exactly which voice has the leading theme. This is followed by the unison group of themes, which leads to a first climax, continually "pierced", as it were, by the trumpet fanfare, until the climax comes to an abrupt halt. The epilogue with its intense oboe melody feels – in stark contrast to the Symphony No. 1, which uses a heroic trombone entrance in the same place – like a moment of silence, of contemplation, of pause, of resignation, before the development commences. In this section, a permanent compression of motivic and thematic elements takes place, caused partially by the combination of parts of different themes. Before the rather unsurprising recapitulation, one of those numerous general pauses occurs, due to which the second symphony has been saddled with the – one has to admit – unfair nickname of the Symphony of Pauses. For in no way do these pauses simply demarcate the borders between the structural elements characteristic of the genre: rather, they constitute an "energy buffer" in which the power of the music continues to throb inaudibly, and is recharged, as it were, with new energy. (In the 1877 version, these pauses are eliminated in various significant places.) The coda leads in two enormous, swelling waves towards its final fff destination, while chanting the fanfare motif from the main theme group.

The Andante – which in the 1871-72 version still occupied the place of the third movement as the Adagio – strikes up the sacral tone that would from now onwards more or less determine all slow movements in Bruckner's symphonies. Not only does Bruckner create a mystical tension by means of the "tritone suspense" of the second theme (which is structured as a double theme, as are the song-themes of the other movements), he also – and mainly – refers to a quasi-religious tone in this movement by means of quotes from the Benedictus (taken from the Mass in F minor, which was premiered in 1872) placed at the transition points before the beginning of the reprise and the coda. Even if one does not understand or recognize the almost literal borrowing of music from the mass as "quotes", the desired chorale-like and sacred character of the music is defined by precisely these sounds. But Bruckner also incorporated the structural layout of this slow movement in the symphonies following his Symphony No. 2 (with the exception of the sixth), thus dictating their form: with two themes in the exposition, the middle section as a kind of development, and a recapitulation excluding the main theme plus coda. Despite its traditional concepts, this is really no longer a sonata form: yet neither is it a pure A-B-A form. Rather, it is a form that applies itself primarily to intensification, with a climax in the recapitulation, followed by a calm and contemplative ending to the movement.

The Scherzo extracts its thematic content from the stamp-bump rhythm of the unison main theme (two quavers on the first beat of the following crotchet impulses), which makes use diastematically of the minor second interval from the main motif of the first movement. Here, the music is wild and aggressive; the rhythmic theme incessantly works its way through the movement; the trio is a Ländler with phases dominated by the woodwind. Bruckner shortened his 1877 version mainly by eliminating the internal repeats. The general pause following the repetition of the Scherzo has a simply surprising and overwhelming effect, when the coda abruptly bursts in and the theme undergoes a final intensification.

Tremendous cuts were made in the finale of the 1877 version, with a mere 613 bars remaining of the original 806. Bruckner also eliminated a few general pauses at various transition points in the symphony, as well as 55 bars in the development (which he replaced by a "new section" [Bruckner]); furthermore, the "Eleison" quote disappeared with the transition to the coda, "as well as the entire first characteristic intensification, including the quotes from the first movement and the finale; so that in the second version, only the final intensification remains, without the intrinsically typical interruption" (Steinbeck). The final movement begins with an intensification, at the end of which the main theme breaks through for the first time in ff, and unison in the orchestra. A quaver-triplet is heard on the first beat, followed by "stamping crotchet notes". A second attempt is also broken off and makes place for the, once again, double-themed song-theme, written in the mediant key of A major, which is again replaced by a kind of fake unison theme, which is merely a variation of the main theme. This presses onward in three attempts to further outbreaks, until a quote from the Kyrie of the Mass in F minor finally resolves the accumulated tension and creates a deep sense of peace. After an extended development and the recapitulation, written in accordance with the rules, Bruckner dedicates himself to the heart of the composition in the coda. Here, he provides the solution not only for the movement, but for the work as a whole: the main themes of the finale and the first movement (with the fanfare-Bruckner-rhythm, which earlier felt strangely out of context in the opening movement) are combined and are brought to a final superlative ending. Bruckner did not consider this work complete without the addition of essential elements from the beginning – namely the main theme and fanfare rhythm from the first movement. And the same was valid for all his following symphonies. The beginning and the end are intermeshed. They are mutually dependent. They fulfil one another; here, in the radiant key of C major. This symphony does not fall between the creative stools – rather, it occupies its own

Hybrydowy format płyty umożliwia odtwarzanie w napędach CD!

Hybrydowy format płyty umożliwia odtwarzanie w napędach CD!