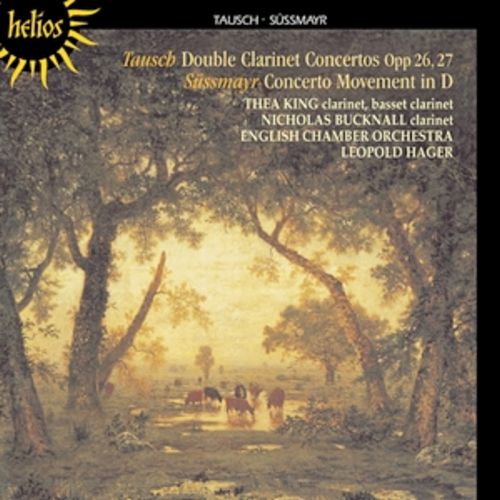

Tausch: Double Clarinet Concertos

Hyperion - CDH 55188

Kompozytor

Franz Wilhelm Tausch (1762-1817)

Franz Wilhelm Tausch (1762-1817)

Utwory na płycie:

00:00/00:00

Error loading: "music/hyperion/cdh55188/cdh55188_01.mp3"

Tausch:

Concerto No 1 in B flat major for two clarinets Op 27

Concerto No 2 in B flat major for two clarinets Op 26

Franz Xaver Süssmayr (1766-1803) & Michael Freyhan (b?):

Concerto movement in D major for basset clarinet

Concerto No 1 in B flat major for two clarinets Op 27

Concerto No 2 in B flat major for two clarinets Op 26

Franz Xaver Süssmayr (1766-1803) & Michael Freyhan (b?):

Concerto movement in D major for basset clarinet

Franz Tausch was born in Heidelberg in 1762 and died in Berlin in 1817. He was one of the earliest of the great clarinet virtuosi. He was taught by his father, Jacob, from the age of six, and two years later became a junior member of the Mannheim orchestra, playing violin and clarinet. When he was only thirteen he joined his father as a full-time member of the orchestra. Mozart would probably have heard Tausch father and son playing in the orchestra when he visited Mannheim in 1777. But by the time he made his famous comment ‘Oh, if only we had clarinets! – you can’t believe what a beautiful effect a symphony with flutes, oboes and clarinets makes’ (letter to his father, 3 December 1778) the Tausches had moved with the court to Munich.

From Munich Franz Tausch began to develop his solo career, finding opportunities to travel. In 1789 he accepted the position of chamber musician to the dowager Queen of Prussia and moved to Berlin. Later he also played in King Frederick William II’s orchestra. After the king’s death in 1797 his successor Frederick William III offered Tausch employment, and he remained in Berlin, founding the Conservatorium der Blasinstrumente (Conservatory for Wind Instruments) in 1805. Tausch had many distinguished pupils, including Crusell and Heinrich Baermann.

Tausch’s qualities were described in an obituary notice in the Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung of 19 March 1817: ‘The son, too [Franz Tausch], acquired a rare perfection on this instrument and won over the whole audience by his seductive, gentle tone and tasteful execution.’ The report adds: ‘He also wrote several concertos and quartets; only a few of the former are published.’

The double concertos were performed from time to time by Tausch with his own son Friedrich Wilhelm. Two such occasions, 21 December 1807 and 6 January 1812, are recorded in the Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung. On the first his eight-year-old daughter also took part, performing a Clementi Fantaisie on the piano; having been a prodigy himself he seems to have wanted the same for his children. It is not certain when his double clarinet concertos were written, or indeed how many he composed. According to Pamela Weston (More Clarinet Virtuosi of the Past, 1977, p253) the second, Op 26, was published by Schlesinger around 1818, but a concerto with the later opus number, Op 27, was written ‘by 1797’ and published by Hummel around the turn of the century. The sequence of opus numbers may not be a reliable guide to the order of composition.

Concerto No 1, Op 27, is scored for strings with two flutes, two bassoons and two horns. The first movement themes have a strong rhythmical foundation, giving the soloists scope for decoration. With the arrival of the second subject the strings melt away, abandoning the soloists to the company of two bassoons. The second movement, a tender Adagio, is interrupted by a menacing switch to the minor, with ominous off-beat semiquavers in the strings. Tranquillity is restored, however, in time for the light-hearted Rondo, which, despite its virtuoso demands on the soloists, qualifies for the present-day category of ‘easy listening’.

The Concerto No 2, Op 26, opens with a slow introduction, supported by the full weight of trumpets and drums. The Allegro section which follows will have none of it, however, and replaces solemnity with lightness and elegance. The soloists, when they enter, are happy to comply. The distribution of musical material is even-handed and each soloist has a share of the cake. After a conscientiously worked-out development section the music slips unobtrusively into the recapitulation. The slow movement is introduced by the strings, but after eight bars they depart, leaving the field to a wind quartet consisting of the two soloists, horn and bassoon. The finale, Rondo, is in essence a theme with variations. If the dotted rhythms of the theme suggest a certain militaristic tendency, it is immediately offset by ornamental and entertaining figuration in the solo parts, showing how far solo clarinet playing had developed by this time.

Franz Xaver Süssmayr was born in Schwanenstadt, Upper Austria, in 1766 and died in Vienna in 1803. Today he is remembered mainly for his completion of Mozart’s Requiem. However, he was a successful composer in his own right whose operas, in particular, enjoyed popularity. His early life was spent at the monastery school in Kremsmünster where he performed as a singer, violinist and organist and began to compose. In July 1788 he settled in Vienna, becoming a pupil and friend of Mozart during the last year or two of Mozart’s life. It is surely no coincidence that the son born to Mozart in July 1791 was christened Franz Xaver, though it is going a bit far to suggest, as some have done, that this is evidence of a particularly intimate friendship between Süssmayr and Mozart’s wife Constanze.

The autograph of Süssmayr’s Clarinet Concerto lies in The British Library, London. The solo part is written for an instrument in A extending down to bottom C, nowadays called the basset clarinet. It was developed by Anton Stadler in the late 1780s but survived for only a few years. Though Mozart wrote his Concerto and Quintet for this instrument, they were published in adaptations for the normal-compass clarinet. Mozart’s autographs have not survived, and the versions for the basset clarinet heard today are modern reconstructions. An authentic example of the instrument’s use by Mozart’s contemporary, Süssmayr, is therefore of especial historical interest.

To be exact, Süssmayr’s Concerto exists in two autographs, one an undated sketch and the other a draft, dated ‘Vienna … January 1792’. Both are incomplete, though Süssmayr obviously expected to finish the draft and fill in the date of completion within the month. They are to be found in a volume of manuscripts of Süssmayr’s works. The volume is noteworthy because it also contains a Mozart autograph – the final pages of the Rondo in A for piano and orchestra, K386 – miscatalogued under Süssmayr’s name until discovered by Alan Tyson in 1980. In his book Mozart, Studies of the Autograph Scores (p262) Tyson writes: ‘The contents of the volume, Add. MS32181, formed part of a large collection of manuscripts by various composers that had been purchased by the British Library (then the British Museum) on 9 February 1884 from the Leipzig antiquarian firm of List and Francke. These manuscripts, catalogued as Add. MS32169–32239, were said to have come from the library of Johann Nepomuk Hummel (1778–1837) …’

On 6 September 1791 Mozart, Stadler and Süssmayr were in Prague for the premiere of La Clemenza di Tito. Stadler played the obbligato parts and Süssmayr, according to the Mozart biography by Georg Nikolaus Nissen, Constanze’s second husband, assisted the hard-pressed Mozart by writing the secco recitatives. There can be little doubt that Süssmayr began to compose his Concerto in Prague, for his earlier sketch was written, to quote Tyson again, ‘on Bohemian paper identical in watermark (though ruled with a slightly different 2-staff rastrum) to that used by Mozart in completing La Clemenza di Tito at Prague in September 1791 – probably Süssmayr’s Concerto was started at that time’ (ibid., p253).

Mozart’s Concerto was completed on his return to Vienna; in a letter to his wife of 7/8 October 1791 he reported that he had just orchestrated almost the whole of the Rondo. A few paragraphs later he writes: ‘Do urge Süssmayr to write something for Stadler, for he has begged me very earnestly to see to this.’ That is how it is translated in The Letters of Mozart and his Family (volume III, p1438), published in 1938 by Emily Anderson. But in the original letter the names have been crossed out, probably by Nissen, for reasons best known to himself. What remains visible reads ‘treibe den … dass er für … schreibt, denn er hat mich sehr darum gebeten’. From the context of the letter Emily Anderson’s interpretation is probably correct.

Despite the encouragement Süssmayr’s Concerto remained but an unfinished sketch. In the meantime Mozart’s own Concerto was given in Prague on 16 October 1791, with Stadler as soloist. A month after Mozart’s death Süssmayr took up his own Concerto again, but something interrupted him. Possibly it was the call from Constanze to complete the unfinished score of Mozart’s Requiem. In any case Stadler had by now embarked on a long tour which kept him away from Vienna until 1796. It would not be hard to imagine that Süssmayr’s enthusiasm faded and he simply lost interest in completing the work.

The musical material of the two autographs is almost sufficient, however, for the construction of a first movement. The earlier sketch extends well into the development section in the solo clarinet part. But the orchestration is essentially complete only as far as the second subject in the soloist’s exposition, at which point it becomes very fragmentary. The subsequent draft, however, is fully orchestrated for strings, two oboes and two horns, but it breaks off altogether at the beginning of the development. It contains alterations to the exposition, some of which are also found squeezed onto spare staves of the sketched version.

To complete the movement it was necessary first to fill out the orchestral part of the development section in accordance with Süssmayr’s sketched suggestions, and then to link it to a recapitulation constructed from Süssmayr’s exposition material – a far more modest challenge than his own completion of Mozart’s Requiem. If Süssmayr had continued with the later draft it might well have contained alterations to the development section, following the pattern of the exposition. Nevertheless it seemed a better principle to use what Süssmayr actually sketched rather than to guess at what he might have written.

The movement opens in the grand manner, leading, however, to gentler and subtler moods. The clarinet writing explores both the lyricism and agility of the instrument, making full use of the low compass, supported by varied and imaginative orchestral textures. It would be unfair to compare Süssmayr’s Concerto with his teacher’s. Süssmayr demonstrates, to his credit, that he is his own man, and occasional technical clumsiness, evident here as in his completion of Mozart’s Requiem, may be regarded as a distinctive feature of his music.

The completion of an unfinished work is bound to arouse misgivings but, since Süssmayr himself showed the way, one might say that he deserves it! After a gestation period of two hundred years it would be time even for a white elephant to be born – how much more a Concerto which has freshness, vitality and charm.

Michael Freyhan © 1991

dawniej CDA 66504 / Recording details: March 1991; St Barnabas's Church, North Finchley, London, United Kingdom; Produced by Martin Compton; Engineered by Antony Howell & Tony Faulkner; Release date: September 2004;

From Munich Franz Tausch began to develop his solo career, finding opportunities to travel. In 1789 he accepted the position of chamber musician to the dowager Queen of Prussia and moved to Berlin. Later he also played in King Frederick William II’s orchestra. After the king’s death in 1797 his successor Frederick William III offered Tausch employment, and he remained in Berlin, founding the Conservatorium der Blasinstrumente (Conservatory for Wind Instruments) in 1805. Tausch had many distinguished pupils, including Crusell and Heinrich Baermann.

Tausch’s qualities were described in an obituary notice in the Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung of 19 March 1817: ‘The son, too [Franz Tausch], acquired a rare perfection on this instrument and won over the whole audience by his seductive, gentle tone and tasteful execution.’ The report adds: ‘He also wrote several concertos and quartets; only a few of the former are published.’

The double concertos were performed from time to time by Tausch with his own son Friedrich Wilhelm. Two such occasions, 21 December 1807 and 6 January 1812, are recorded in the Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung. On the first his eight-year-old daughter also took part, performing a Clementi Fantaisie on the piano; having been a prodigy himself he seems to have wanted the same for his children. It is not certain when his double clarinet concertos were written, or indeed how many he composed. According to Pamela Weston (More Clarinet Virtuosi of the Past, 1977, p253) the second, Op 26, was published by Schlesinger around 1818, but a concerto with the later opus number, Op 27, was written ‘by 1797’ and published by Hummel around the turn of the century. The sequence of opus numbers may not be a reliable guide to the order of composition.

Concerto No 1, Op 27, is scored for strings with two flutes, two bassoons and two horns. The first movement themes have a strong rhythmical foundation, giving the soloists scope for decoration. With the arrival of the second subject the strings melt away, abandoning the soloists to the company of two bassoons. The second movement, a tender Adagio, is interrupted by a menacing switch to the minor, with ominous off-beat semiquavers in the strings. Tranquillity is restored, however, in time for the light-hearted Rondo, which, despite its virtuoso demands on the soloists, qualifies for the present-day category of ‘easy listening’.

The Concerto No 2, Op 26, opens with a slow introduction, supported by the full weight of trumpets and drums. The Allegro section which follows will have none of it, however, and replaces solemnity with lightness and elegance. The soloists, when they enter, are happy to comply. The distribution of musical material is even-handed and each soloist has a share of the cake. After a conscientiously worked-out development section the music slips unobtrusively into the recapitulation. The slow movement is introduced by the strings, but after eight bars they depart, leaving the field to a wind quartet consisting of the two soloists, horn and bassoon. The finale, Rondo, is in essence a theme with variations. If the dotted rhythms of the theme suggest a certain militaristic tendency, it is immediately offset by ornamental and entertaining figuration in the solo parts, showing how far solo clarinet playing had developed by this time.

Franz Xaver Süssmayr was born in Schwanenstadt, Upper Austria, in 1766 and died in Vienna in 1803. Today he is remembered mainly for his completion of Mozart’s Requiem. However, he was a successful composer in his own right whose operas, in particular, enjoyed popularity. His early life was spent at the monastery school in Kremsmünster where he performed as a singer, violinist and organist and began to compose. In July 1788 he settled in Vienna, becoming a pupil and friend of Mozart during the last year or two of Mozart’s life. It is surely no coincidence that the son born to Mozart in July 1791 was christened Franz Xaver, though it is going a bit far to suggest, as some have done, that this is evidence of a particularly intimate friendship between Süssmayr and Mozart’s wife Constanze.

The autograph of Süssmayr’s Clarinet Concerto lies in The British Library, London. The solo part is written for an instrument in A extending down to bottom C, nowadays called the basset clarinet. It was developed by Anton Stadler in the late 1780s but survived for only a few years. Though Mozart wrote his Concerto and Quintet for this instrument, they were published in adaptations for the normal-compass clarinet. Mozart’s autographs have not survived, and the versions for the basset clarinet heard today are modern reconstructions. An authentic example of the instrument’s use by Mozart’s contemporary, Süssmayr, is therefore of especial historical interest.

To be exact, Süssmayr’s Concerto exists in two autographs, one an undated sketch and the other a draft, dated ‘Vienna … January 1792’. Both are incomplete, though Süssmayr obviously expected to finish the draft and fill in the date of completion within the month. They are to be found in a volume of manuscripts of Süssmayr’s works. The volume is noteworthy because it also contains a Mozart autograph – the final pages of the Rondo in A for piano and orchestra, K386 – miscatalogued under Süssmayr’s name until discovered by Alan Tyson in 1980. In his book Mozart, Studies of the Autograph Scores (p262) Tyson writes: ‘The contents of the volume, Add. MS32181, formed part of a large collection of manuscripts by various composers that had been purchased by the British Library (then the British Museum) on 9 February 1884 from the Leipzig antiquarian firm of List and Francke. These manuscripts, catalogued as Add. MS32169–32239, were said to have come from the library of Johann Nepomuk Hummel (1778–1837) …’

On 6 September 1791 Mozart, Stadler and Süssmayr were in Prague for the premiere of La Clemenza di Tito. Stadler played the obbligato parts and Süssmayr, according to the Mozart biography by Georg Nikolaus Nissen, Constanze’s second husband, assisted the hard-pressed Mozart by writing the secco recitatives. There can be little doubt that Süssmayr began to compose his Concerto in Prague, for his earlier sketch was written, to quote Tyson again, ‘on Bohemian paper identical in watermark (though ruled with a slightly different 2-staff rastrum) to that used by Mozart in completing La Clemenza di Tito at Prague in September 1791 – probably Süssmayr’s Concerto was started at that time’ (ibid., p253).

Mozart’s Concerto was completed on his return to Vienna; in a letter to his wife of 7/8 October 1791 he reported that he had just orchestrated almost the whole of the Rondo. A few paragraphs later he writes: ‘Do urge Süssmayr to write something for Stadler, for he has begged me very earnestly to see to this.’ That is how it is translated in The Letters of Mozart and his Family (volume III, p1438), published in 1938 by Emily Anderson. But in the original letter the names have been crossed out, probably by Nissen, for reasons best known to himself. What remains visible reads ‘treibe den … dass er für … schreibt, denn er hat mich sehr darum gebeten’. From the context of the letter Emily Anderson’s interpretation is probably correct.

Despite the encouragement Süssmayr’s Concerto remained but an unfinished sketch. In the meantime Mozart’s own Concerto was given in Prague on 16 October 1791, with Stadler as soloist. A month after Mozart’s death Süssmayr took up his own Concerto again, but something interrupted him. Possibly it was the call from Constanze to complete the unfinished score of Mozart’s Requiem. In any case Stadler had by now embarked on a long tour which kept him away from Vienna until 1796. It would not be hard to imagine that Süssmayr’s enthusiasm faded and he simply lost interest in completing the work.

The musical material of the two autographs is almost sufficient, however, for the construction of a first movement. The earlier sketch extends well into the development section in the solo clarinet part. But the orchestration is essentially complete only as far as the second subject in the soloist’s exposition, at which point it becomes very fragmentary. The subsequent draft, however, is fully orchestrated for strings, two oboes and two horns, but it breaks off altogether at the beginning of the development. It contains alterations to the exposition, some of which are also found squeezed onto spare staves of the sketched version.

To complete the movement it was necessary first to fill out the orchestral part of the development section in accordance with Süssmayr’s sketched suggestions, and then to link it to a recapitulation constructed from Süssmayr’s exposition material – a far more modest challenge than his own completion of Mozart’s Requiem. If Süssmayr had continued with the later draft it might well have contained alterations to the development section, following the pattern of the exposition. Nevertheless it seemed a better principle to use what Süssmayr actually sketched rather than to guess at what he might have written.

The movement opens in the grand manner, leading, however, to gentler and subtler moods. The clarinet writing explores both the lyricism and agility of the instrument, making full use of the low compass, supported by varied and imaginative orchestral textures. It would be unfair to compare Süssmayr’s Concerto with his teacher’s. Süssmayr demonstrates, to his credit, that he is his own man, and occasional technical clumsiness, evident here as in his completion of Mozart’s Requiem, may be regarded as a distinctive feature of his music.

The completion of an unfinished work is bound to arouse misgivings but, since Süssmayr himself showed the way, one might say that he deserves it! After a gestation period of two hundred years it would be time even for a white elephant to be born – how much more a Concerto which has freshness, vitality and charm.

Michael Freyhan © 1991

dawniej CDA 66504 / Recording details: March 1991; St Barnabas's Church, North Finchley, London, United Kingdom; Produced by Martin Compton; Engineered by Antony Howell & Tony Faulkner; Release date: September 2004;